Yes, I haven’t written anything in a long time. It’s not for lack of time to write, but more a lack of time to see movies in the theater. With two musicals I’m helping with, plus five deaths of folks I loved (including my mother-in-law), seeing films got bumped to the bottom of the pile. But due to my wife’s accommodations, even while sick, I was able to catch the last showing of the film in a decent theater the day before it went away.

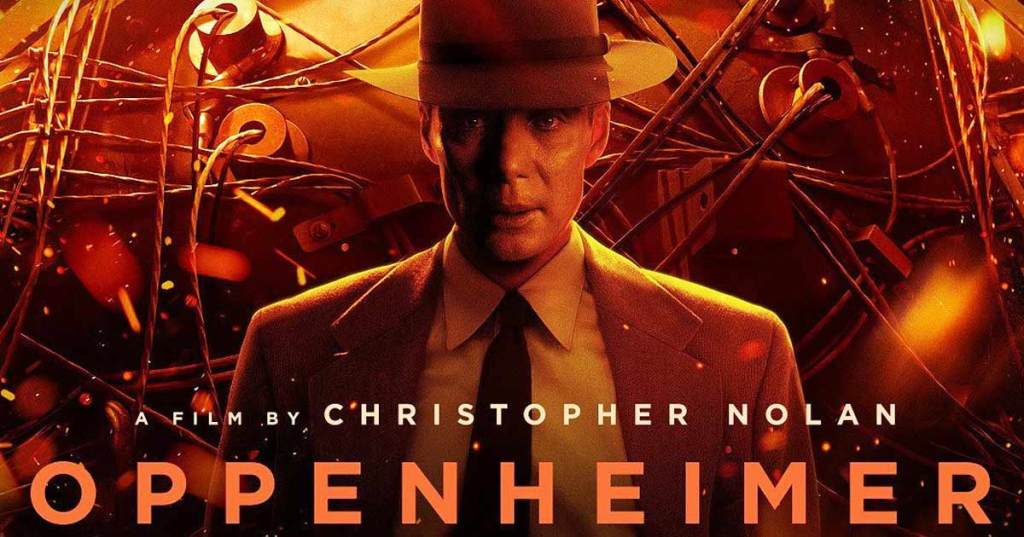

My recommendation: Don’t see this on your TV at home. Wait until the Oscar nominations come out and seek out whatever theater in your area is showing it. It’s a spectacular film, in several definitions of the word. As with many other Christopher Nolan films, it is a roaring combination of images and sound and music and editing—not just a viewing but an experience. I wish I’d seen it in our local IMAX theater, but hey, reread paragraph one.

It’s exciting to see Nolan working like this—for two reasons. One, he is a mainstream director still experimenting with what film can do. In an age of superhero movies, loud action flicks (I can’t quite call them films), and loads of kids’ entertainments that are just fine for their audience, having an artist still engaging with film form like this is encouraging. Oppenheimer’s story can be seen as “all over the place” for those that prefer a chronological approach to a biopic. But this is not a biopic. Like many these days, it may address past and future, but the focus is on one particular episode in a person’s life—in this case, J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work on the Manhattan project and all thoughts and emotions pertaining thereto. It’s a huge artistic reach that works; I thought of The Tree of Life as I watched it, a film that also reaches for the stars. The Tree of Life is a flawed masterpiece that just missed greatness. Oppenheimer reaches nearly as high, but succeeds because it’s more focused and cohesive.

Two, finally, finally, Nolan has kept his control of film and his wildly conceptual brain under control, and in service to the story he is telling. I can view his earlier films as experiments that put sight, sound and film design above the narrative (Memento, Tenet, and certainly Inception). In spite of the head-banging time device he used in Dunkirk, I felt with that film that he was moving toward actual human emotion at times, and that his respect for the tale he was telling was growing. Some folks who strongly appreciate the experimenter in Nolan may bemoan the new balance between narrative and spectacle. But Oppenheimer shows how a film can be experimental and accessible (and enjoyable) at the same time. It’s a wild ride at times, but never goes off the rails.

Lead actor Cillian Murphy has been a strong presence in earlier Nolan films (Batman Begins, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, Inception, and Dunkirk), and here he is given an ostensibly star-making role that probably won’t make him a star. He is a well-respected actor and will continue to be, but this is a movie about what happens TO someone rather than what a person is able to accomplish. Murphy is a rather recessive screen presence, which works well here with all the people and action flying around him. His role is similar to that of Good Night, and Good Luck’s central character of Edward R. Murrow, played by respected actor/non-star David Strathairn in what in all likelihood will be the defining role of his career. Murphy does everything he is asked to do, and does it well, but it is Nolan that holds the film together, not any one actor—not even the lead. It may even garner Murphy an Oscar nomination, but there is no way he would win.

One way Nolan keep things moving beyond his lead is his casting of most of the other main characters. As in Sam Mendes’ 1917, important characters are played by important stars. The two biggest are Iron Man/Tony Stark and Good Will Hunting/Jason Bourne—oops, I mean Robert Downey Jr. and Matt Damon. Their entrances are somewhere between a surprising bump in the film and a shock. Such major stars in such different roles actually works for this film, however, as they both bite into their characters with gusto, and their star power brings us right into their worlds. (Slight spoiler alert—one character starts as a baddie and ends up a goodie, and the other follows the opposite arc.) They do what stars are supposed to—they draw us in and give us a strong initial impression. In Damon’s case, for example, a character that we might have resisted is played by…Matt Damon, for heaven’s sake. As much as we might be put off by first impressions, can we really hate a character played by one of our most lovable actors?

Current “It” girl Florence Pugh (Don’t Worry Darling, Black Widow, Midsommar) has such a strong cinematic presence that it threatens to overwhelm both the gratuitousness of her sex scenes and the ambiguity (a nicer word than indistinctness) of her character. The future Oscar winner owns the scenes she is in, but threatens to imbalance the film at times with her cinematic authority.

Another star surprise that I first thought was more of a stunt than anything else is Emily Blunt as Oppenheimer’s wife. Blunt is an accomplished actress, yet I was wondering how she would deliver as an actress and disappear into her character. Though the film goes a big overboard in visually signaling her character’s problem with alcohol, Blunt has a beautifully realized arc to her character, and changes perhaps more than any other character in the film. Damon and Downey Jr., and even Murphy don’t change or develop as much as they age and are slowly unveiled in terms of personality and agenda as the film progresses. (Note: The British Blunt and the Irish Murphy do a great job with their American accents.)

But these stars are only the beginning. Alden Ehrenreich (Hail, Caesar! and Solo: A Star Wars Story) may well have been cast years ago based on his possible future star power. But he’s not there yet, so his impact is minimal as a star, while his performance is just acceptable. Add in Jason Clarke, Tony Goldwyn, Scott Grimes, Tim DeKay, Tom Conti (as Einstein!), David Krumholtz, Matthew Modine, and personal favorite James D’Arcy, and the viewer has a few too many bumpy “I know that face moments,” while the casting of Kenneth Branagh and yes, Rami Malek, simply border on the distracting. Of course they are good actors, but they are bigger stars than their parts allow.

The music by Ludwig Göransson (“The Mandalorian,” an Oscar for Black Panther) isn’t quite in the same musical category as Jonny Greenwood’s in There Will Be Blood. But like the music in that earlier film, the music here eschews the classical studio approach with a vengeance, and works with and against the image, and often as simply an equal partner with the visuals, neither undermining nor overwhelming, but strongly claiming its own place.

Much has been written about the special effects, with perhaps too much attention paid to the more classical, less CGI approach than to their actual place in the film. But the cinematography by Hoyte Van Hoytema (Tenet, Nope, Ad Astra, Dunkirk), along with the effects, are of one piece (albeit a mosaic), and are stunning. As a Rochesterian, I could nerd out on the use of actual film, and specifically the special Kodak film used for the beautiful black-and-white sequences. Again, Nolan is one of the few working in film, and we can only applaud a great director who continues to use film, yet pushes its limits.

There are several stories here, yet they all come together. We have the story of a brilliant scientist and womanizer, the people in his personal life, and how he is both honored and unfairly maligned. Then we have the story of the atomic (and yes, the hydrogen) bomb, and specifically the Manhattan project, from theorizing to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We also have a story of fascism and especially communism, and the latter’s impact on the fears of America. Then of course there are the overarching moral and political quandaries with the Pandora’s Box that is opened with the development of the bomb.

Nolan manages to keep all these strands working without any one aspect falling to the side or becoming lopsided. I don’t know of another director other than Terrence Malick who could have pulled this off. Nolan operates on a level that might not be to everyone’s taste (see the success of Barbie, etc.), but the fact that a three-hour movie about a scientist has made nearly a billion dollars is encouraging.